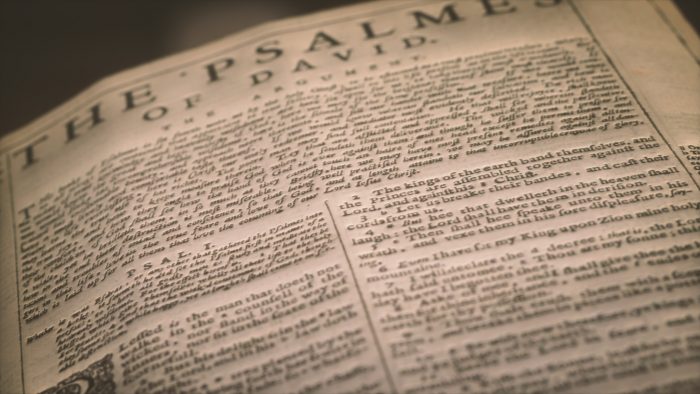

When it was first printed, the Geneva Bible was the most reader-friendly version of the Bible ever translated. Its numerous innovations made it ideal for the common reader. What sets the Geneva Bible apart? I recently sat down with Dr. David A. Bennett, a local antique Bible collector and amateur historian of Bible history, to find out.

An Interview with Dr. David A Bennett:

Q: Can you give us a brief history of the Geneva Bible?

From 1555 to 1558

During Queen Mary’s reign, from 1555 and 1558, she burned 288 Protestant ministers at the stake for their denial of one tenet or another of the Roman religion. During the 1550s, when the Protestants of England were under such fierce persecution, many of their minsters fled to Geneva, Switzerland, to a theocracy maintained by Calvin and his contemporaries. Such a blessed company of Protestant theologians and scholars produced a Bible in 1560 aptly called the Geneva Bible. John Calvin, John Knox, Myles Coverdale, John Foxe, and several other Reformers may have collaborated on the Bible. However, most of the work was done by William Whittingham. He was the pastor of the Geneva Church and a dear friend of John Calvin.

1558 and Beyond

The Geneva New Testament of 1558 was barely off the press when work began on a revision of the entire Bible. This process took two more years. The new translation was checked with Theodore Beza’s earlier work and with the Greek text. In 1560, a complete revised Bible was published, “translated according to the Hebrew and Greek, and conferred with the best translations in divers languages”.

Not only was the Geneva Bible innovative and influential, it has a remarkable history. The Geneva Bible was a product of vicious persecution endured by the English reformers. Its marginal notes edified the people and infuriated a King. While previous English translations failed to capture the hearts of the reading public, the Geneva Bible was instantly popular. Between 1560 and 1644 at least 144 editions appeared. Even forty years after the publication of the King James Bible, the Geneva Bible continued to be the Bible of the home.

Two of the prime attractions of the Geneva Bible were its cost – the average cost of this printed Bible was less than a week’s wages for a working man – and the commentary amply interspersed throughout the Bible. The Geneva Bible was the first study Bible ever printed, a fact which both endeared it to the laity and irritated the clergy and monarchy, as neither archbishop nor king was allotted the god-like status each sought. The Bible brought to the American colonies by the Pilgrims in 1620 was their much-beloved 1599 Geneva Bible.

During the decades following the publication of the King James Bible in 1611, both political and commercial meddling by monarch and bishop was implemented to finally subvert the influence of the Geneva Bible.

Q: What sets the Geneva Bible apart from other translations?

The Geneva Bible was a Bible of firsts. It was the first..

- Entire Bible in English translated from the original languages, not depending upon the Latin Vulgate at all

- English Bible translation intended for use by lay Christians, following on the heels of Martin Luther’s 1534 German Bible for the German laity

- Bible in English to use contemporary verse divisions

- To use italicized words where English required more than a literal Greek rendering

- Bible in the English language with commentary, so it’s the first study Bible

- English Bible translated by a committee and not an individual

Q: Besides the study notes, are there any substantial ways in which the Geneva text differs from that of the KJV?

Using the verbiage of types and antitypes, the Geneva Bible was the antitype or fulfillment of Tyndale’s pioneering work. Additionally, it was the type or prototype of the King James Bible to come 50 years later. Fully 80% of the books Tyndale translated into English are present in the Geneva Bible. Also, 80% of the King James Bible is attributed to the Geneva Bible – minus the marginal commentary!

Quite frankly, its marginal notes both fanned the flames of the Geneva Bible’s success, but also resulted in its eventual demise and the succession of the King James Bible as the de facto English Bible for centuries to come. Had not the marginal commentary been so polarizing, there is good reason to suspect that neither the Bishop’s Bible nor even the King James Bible would ever have been conceived.

Q: How does the Tolle Lege edition that Olive Tree is releasing differ from the original 1599 Geneva Bible?

Today’s readers will find it difficult to read the original print edition. This is due to its archaic typography and outdated spellings and word usage. For example, it is quite interesting to notice the progression of the English language, during which English acquired the use of the letter “j” to use in appropriate places where only “i” had been used before, and the consistent delineation of “v” and “u” as we know today.

The Tolle Lege Press edition removes the major obstacles for the contemporary reader. It returns this historic Bible to its rightful place of influence and importance. The original 1599 Geneva Bible gave God’s Word back to the people, and Tolle Lege Press desires that the tradition continue.

Thanks to Dr. Bennett for his time and insights into the 1599 Geneva Bible.

Get Your Own Copy!

You can find the 1599 Geneva Bible in our store. Get your own copy today to keep learning more about it!

0 Comments