Wanting to learn more about Gregory the Great? Look no further! Below you’ll find helpful information we gathered from some fantastic resources. First, we’ll do a quick Q&A. Next, we’ll take it a bit more in-depth. Lastly, we’ll give you the ability to hear from Gregory himself. Even if you don’t have an overwhelming desire to learn about this topic, this post can show you the usefulness of the Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity and the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture.

QUICK OVERVIEW of GREGORY THE GREAT

Below are some common questions and quick answers. For more in-depth information, keep scrolling!

Q&A

540 a.d.

September 3, 590 a.d.

March 12, 604 a.d. in Rome

He wrote a 35-book interpretation of Job, in four points of view: literal, allegorical, typological, and moral. He founded six monasteries, collaborated with Augustine, worked under Pelagius, and succeeded him as pope.

He took on the duties of the government that were being neglected, like feeding the community. He also attempted to reform the church in a monastic direction.

Tiny Biography

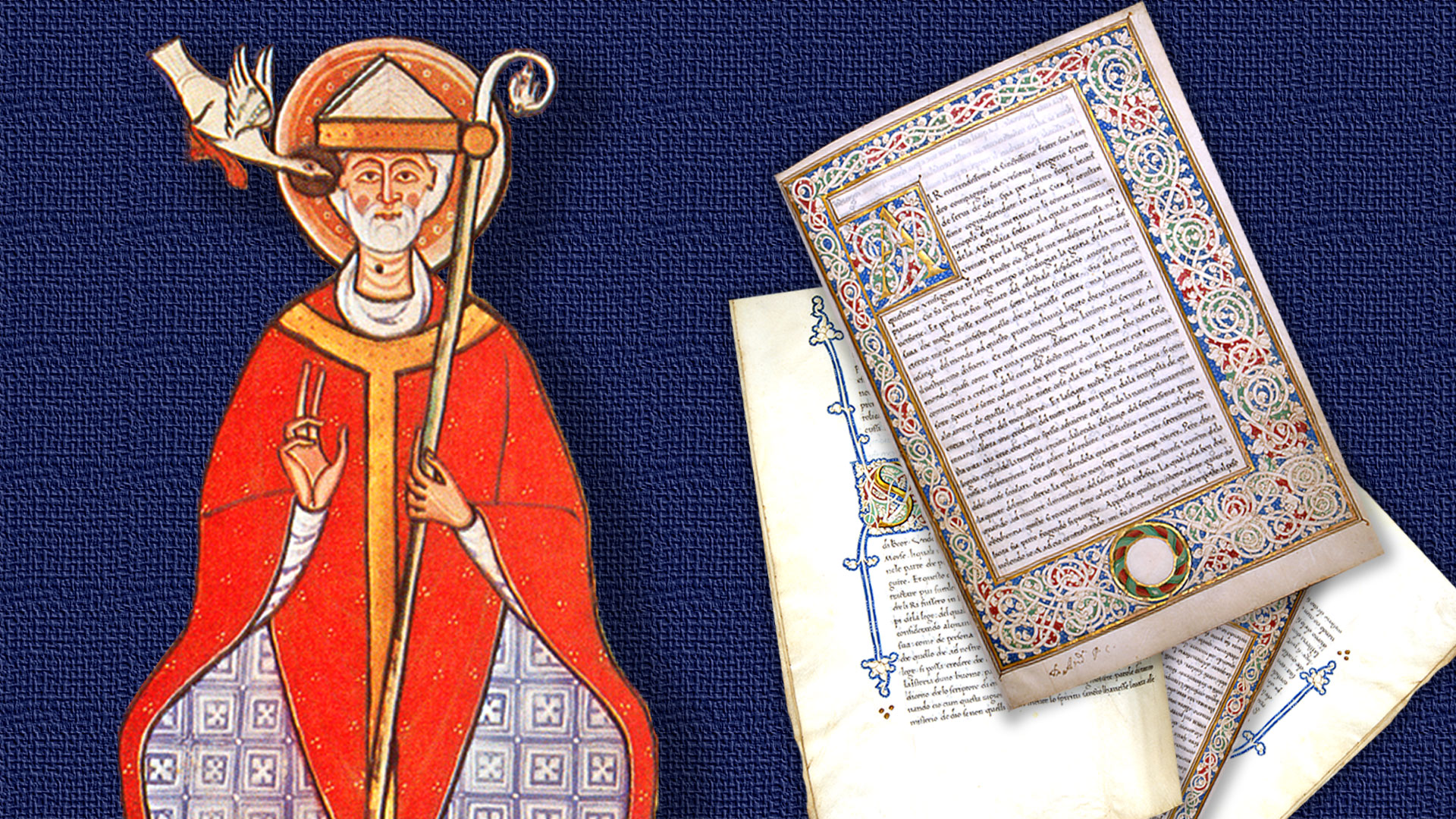

Pope from 590, the fourth and last of the Latin “Doctors of the Church.” He was a prolific author and a powerful unifying force within the Latin Church, initiating the liturgical reform that brought about the Gregorian Sacramentary and Gregorian chant.

Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture

MORE IN-DEPTH LOOK AT GREGORY THE GREAT

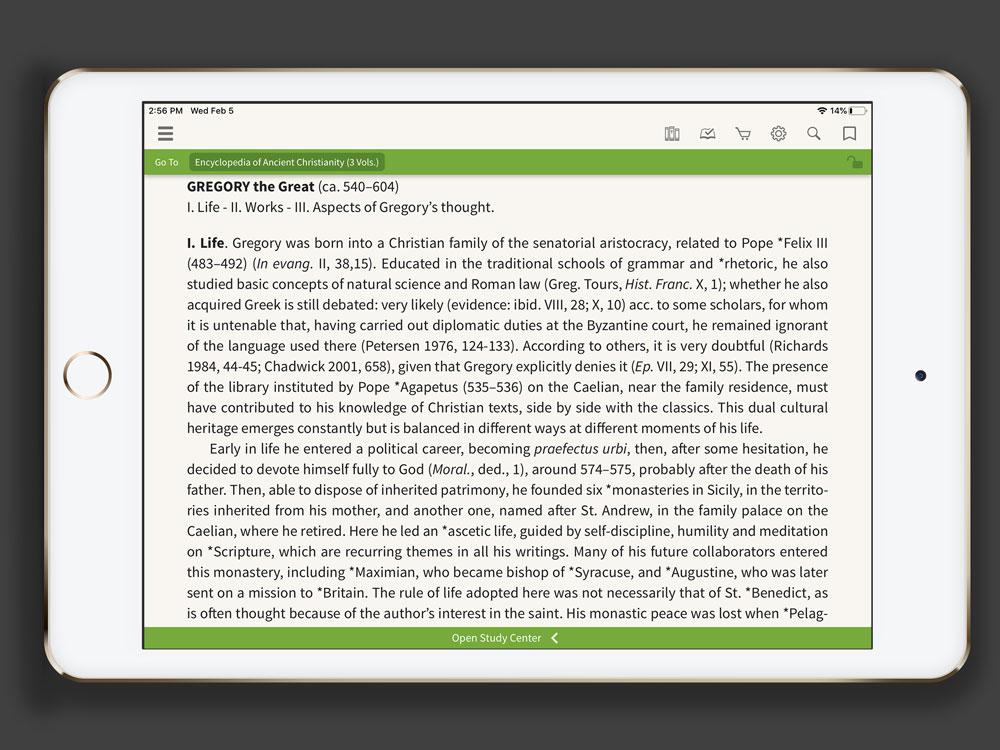

The Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity goes incredibly in-depth on Gregory the Great’s life. We can’t share it all here, but below you’ll find a few paragraphs from the resource. Also, we’ve removed the citations from the sentences for easier reading here on the blog. But you can see them by looking at the screenshot. This is a very academic resource!

Pope Gregory’s Life

Becoming a Monk

Early in life he entered a political career, becoming praefectus urbi, then, after some hesitation, he decided to devote himself fully to God, around 574–575, probably after the death of his father. Then, able to dispose of inherited patrimony, he founded six monasteries in Sicily, in the territories inherited from his mother, and another one, named after St. Andrew, in the family palace on the Caelian, where he retired.

Here he led an ascetic life, guided by self-discipline, humility and meditation on Scripture, which are recurring themes in all his writings. Many of his future collaborators entered this monastery, including Maximian, who became bishop of Syracuse, and Augustine, who was later sent on a mission to Britain. The rule of life adopted here was not necessarily that of St. Benedict, as is often thought because of the author’s interest in the saint.

Becoming a Deacon

His monastic peace was lost when Pelagius II ordained him deacon and sent him to Constantinople as apocrisarius to the emperor, Tiberius II at first, then from 582 Maurice. He was sent in order to solicit aid against the Longobards in Italy, who had arrived on the peninsula some ten years prior, and continued their incursions into the territories of the Byzantine Empire, including Rome.

In these years (ca. 579–586) to his diplomatic efforts was added the doctrinal controversy with the patriarch of Constantinople, Eutyches, on the resurrection of the body, which ended with the imperial approval of the theory supported by Gregory.

Meanwhile, he became deeply involved in the interpretation of the book of Job, at the request of his group of friends, who were united by common spiritual interests. Among them was Leander of Seville. Gregory remained in contact with him after his return to Rome.

Becoming the Pope

There, Pelagius made use of Gregory in the political and ecclesiastical problems concerning, among other things, the Lombards and the question of the Three Chapters (see the letter written to the bishops of Istria by Gregory on behalf of Pelagius).

The pontiff died 7 February 590, struck by bubonic plague following the flood of the Tiber in 589; a week later, Gregory organized a procession in the city, bound for S. Maria Maggiore, to implore from God the end of the plague.

Already esteemed for his role under Pelagius, he was acclaimed by the Roman people as Pelagius’s successor and, after a few months, received imperial approval, followed by the episcopal consecration on 3 September 590.

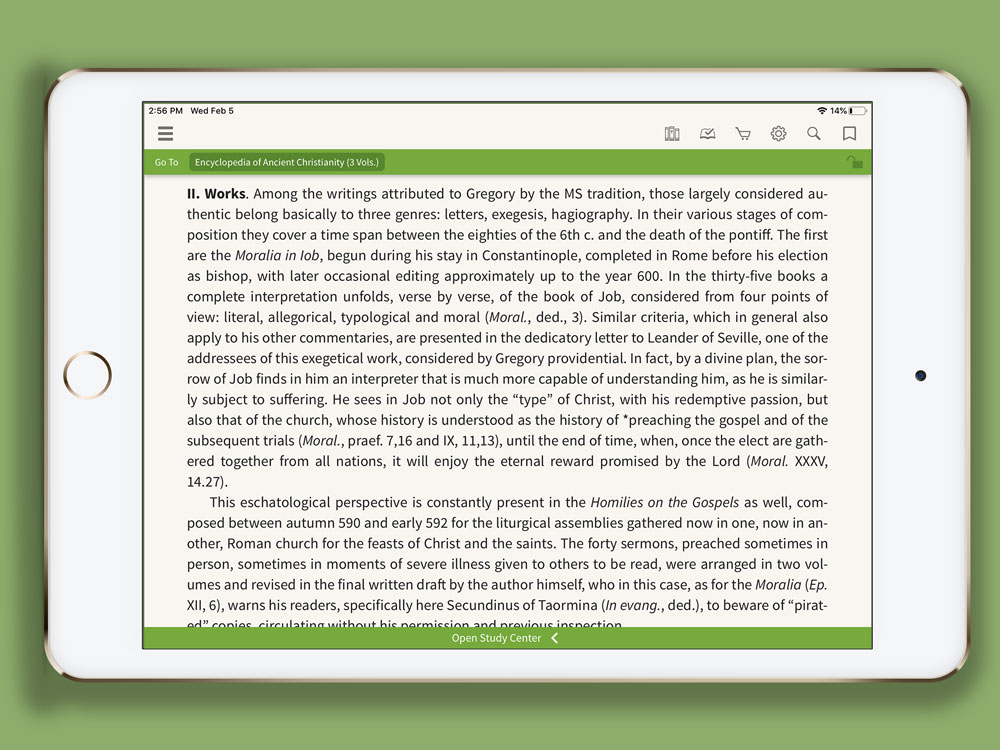

Gregory the Great’s Writings

Among the writings attributed to Gregory by the MS tradition, those largely considered authentic belong basically to three genres: letters, exegesis, hagiography. In their various stages of composition they cover a time span between the eighties of the 6th c. and the death of the pontiff.

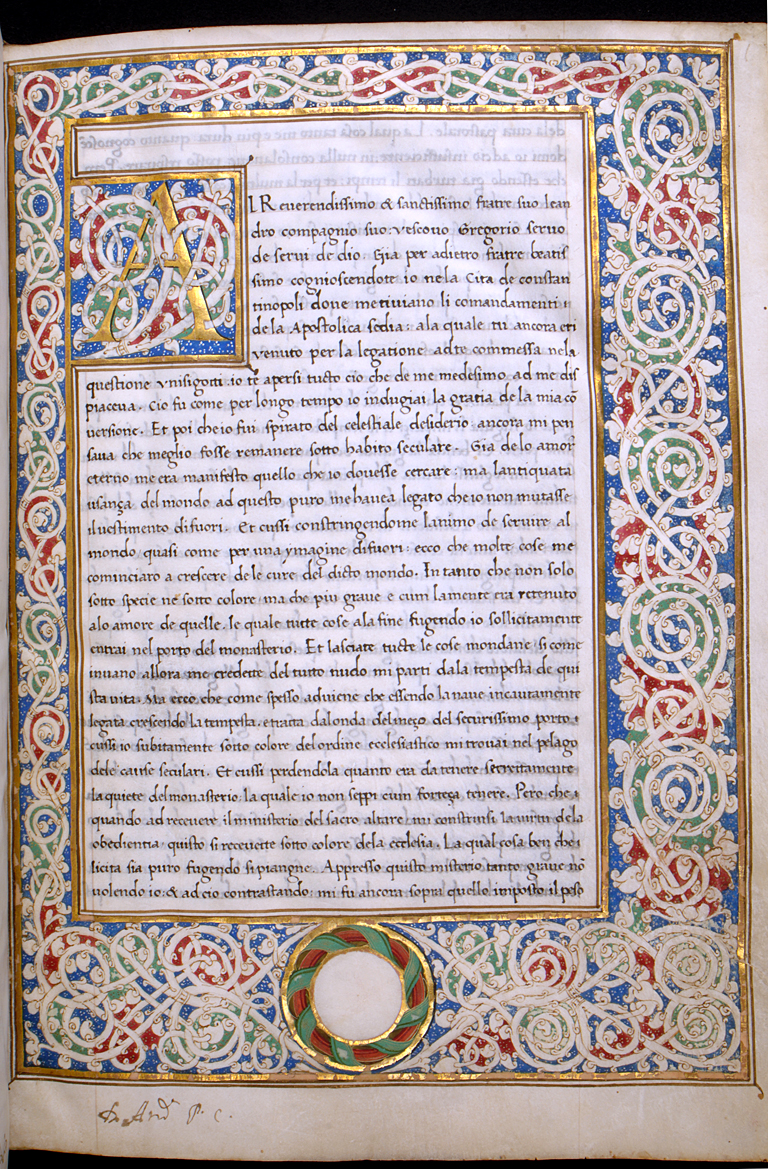

The first are the Moralia in Iob, begun during his stay in Constantinople, completed in Rome before his election as bishop, with later occasional editing approximately up to the year 600. In the thirty-five books a complete interpretation unfolds, verse by verse, of the book of Job, considered from four points of view: literal, allegorical, typological and moral.

Similar criteria, which in general also apply to his other commentaries, are presented in the dedicatory letter to Leander of Seville, one of the addressees of this exegetical work, considered by Gregory providential.

In fact, by a divine plan, the sorrow of Job finds in him an interpreter that is much more capable of understanding him, as he is similarly subject to suffering. He sees in Job not only the “type” of Christ, with his redemptive passion, but also that of the church, whose history is understood as the history of preaching the gospel and of the subsequent trials, until the end of time, when, once the elect are gathered together from all nations, it will enjoy the eternal reward promised by the Lord.

Read Gregory the Great’s Thoughts on Job

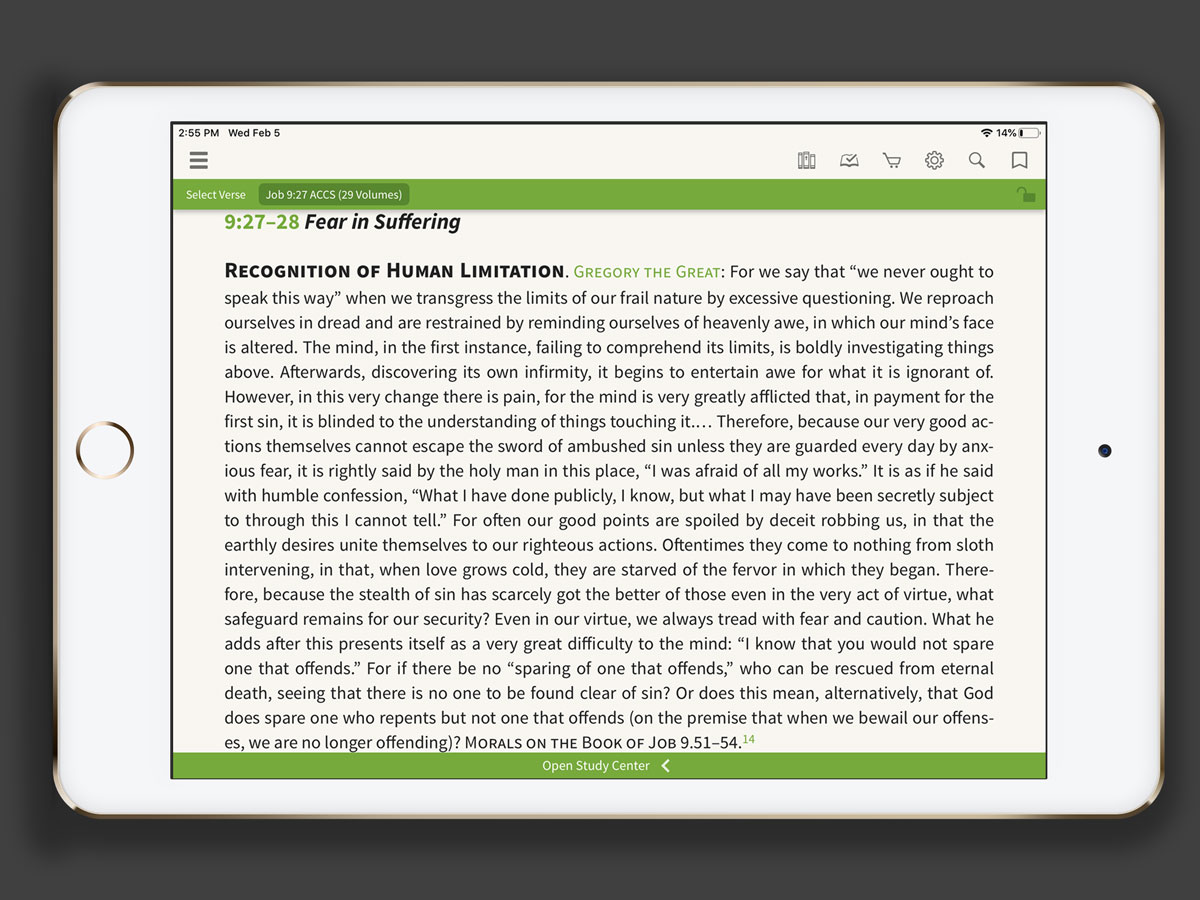

The Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture contains excerpts of the Church father’s writings for nearly every passage of the Bible. Below you’ll find Gregory’s thoughts on Job 9:27-28. Originally, this excerpt is from his work entitled Morals on the Book of Job.

Scripture

If I say, ‘I will forget my complaint,

Job 9:27-28

I will change my expression, and smile,’

I still dread all my sufferings,

for I know you will not hold me innocent.

Recognition of Human Limitation, Gregory the Great

For we say that “we never ought to speak this way” when we transgress the limits of our frail nature by excessive questioning. We reproach ourselves in dread and are restrained by reminding ourselves of heavenly awe, in which our mind’s face is altered. The mind, in the first instance, failing to comprehend its limits, is boldly investigating things above. Afterwards, discovering its own infirmity, it begins to entertain awe for what it is ignorant of.

However, in this very change there is pain, for the mind is very greatly afflicted that, in payment for the first sin, it is blinded to the understanding of things touching it.… Therefore, because our very good actions themselves cannot escape the sword of ambushed sin unless they are guarded every day by anxious fear, it is rightly said by the holy man in this place, “I was afraid of all my works.”

It is as if he said with humble confession, “What I have done publicly, I know, but what I may have been secretly subject to through this I cannot tell.”

For often our good points are spoiled by deceit robbing us, in that the earthly desires unite themselves to our righteous actions. Oftentimes they come to nothing from sloth intervening, in that, when love grows cold, they are starved of the fervor in which they began. Therefore, because the stealth of sin has scarcely got the better of those even in the very act of virtue, what safeguard remains for our security? Even in our virtue, we always tread with fear and caution.

What he adds after this presents itself as a very great difficulty to the mind: “I know that you would not spare one that offends.” For if there be no “sparing of one that offends,” who can be rescued from eternal death, seeing that there is no one to be found clear of sin?

Or does this mean, alternatively, that God does spare one who repents but not one that offends (on the premise that when we bewail our offenses, we are no longer offending)?

LEARN MORE ABOUT GREGORY THE GREAT AND OTHER ANCIENT CHRISTIANS

We used two amazing resources in our research for this post.

First, we used the Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity.

It covers eight centuries of the Christian church! With over 3,000 entries by a team of 266 scholars from 26 countries, this resource is reliable, academic, and representative of many different traditions.

What kind of information does this resource have? Everything under the sun! The encyclopedia references archaeology, art and architecture, cultural studies, ecclesiology, geography, history, philosophy, theology, and more.

Second, we used the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture.

This commentary is an ecumenical project, promoting a vital link of communication between the varied Christian traditions of today and their common ancient ancestors in the faith. On this shared ground, we listen as leading pastoral theologians of seven centuries gather around the text of Scripture and offer their best theological, spiritual and pastoral insights.

0 Comments